HOMEWesley Britton’s Books,

|

Spies on FilmSpies on Television & RadioSpies in History & LiteratureThe James Bond Files |

|

Spies in History & Literature ~ T.H.E. Hill’s Voices

Under Berlin – A Spy Novel That Breaks All the Molds

By Wesley Britton  For 28 years, the most iconic symbol of the Cold War was the Berlin Wall. After its construction beginning on August 13, 1961 until its dismantlement in the fall of 1989, U.S. Presidents – notably Kennedy and Reagan – pointed to the wall as the most visible representation of the totalitarian nature of the Soviet bloc. The divided city was also the epicenter of espionage literature and films. The Wall, the Brandenburg Gate, and the most famous crossing point – “Checkpoint Charlie” – were important settings in the works of, for but a few examples, John Le Carré (The Spy Who Came in From the Cold) and Len Deighton (Funeral in Berlin). In fact, virtually every novel in Deighton’s Bernard Sampson family saga centered in Berlin with Western spies slipping in and Eastern defectors sneaking out, making going over, under, or through the Wall an ongoing sport in the covert duels between intelligence agencies. But one episode in this history has never been of much interest to filmmakers or novelists. From February 1954 to April 1956, “Operation Gold” – as the Yanks dubbed it – or “Operation Stopwatch” – as the Brits called it – was a joint operation of the CIA and the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). Together, they dug a tunnel below the border between the Western sector of Berlin and the Soviet section to tap into the landline communications between Group of Soviet Forces Germany and their masters in Moscow. The most infamous personage connected to this most-elaborate of phone-taps was George Blake, a mole inside British intelligence who blew the whistle on the project even before it began. Over the years, many have wondered – did the Soviets use the opportunity to provide disinformation to the West or did they allow the line to stay open to keep Blake’s cover secure? After all, he wasn’t uncovered until 1961. Such a scenario might not seem fertile ground for literature focusing on spies, counter-spies, and wiley intelligence chiefs playing coded chess with their adversaries. If one were to follow the formulas of most spy fiction, the Berlin Tunnel might not have all the drama of a best-selling Ludlum pot-boiler. However, if a writer was to take his attention off spy vs. spy molds and focus instead on the cryptographers, linguists, and analysts sifting through intercepted intelligence, then a long neglected cadre of Cold War warriors could be something fresh to explore. Does the image of code-breakers sitting in dusty rooms wearing headphones while scribbling on notepads sound a bit on the dry side? Not in the hands of T.H.E. Hill. His 2008 Voices Under Berlin: The Tale of a Monterey Mary is, in fact, perhaps the funniest spy book ever written. It’s not a parody or satire of the 007 mythos nor is it a continuation of themes in the novels by the likes of Graham Greene or Eric Ambler poking fun at the ineptitude of clandestine services. Still, in the tradition of Greene and Ambler, Voices Under Berlin contains many literate qualities that make it a work of special consideration, worthy of an audience much broader than that of espionage enthusiasts or those interested in Cold War history. In fact, one indication of the book’s quality is that it was among the award winners at the July 2008 Hollywood Book Festival, a very rare honor for a spy novel.

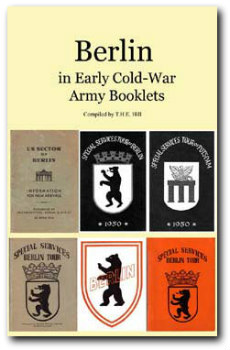

The Berlin tunnel Hill’s humor, justly, has been compared with that of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 and Richard Hooker’s M*A*S*H. Like Heller and Hooker, Hill’s characters and comic situations draw from military life, in this case playing with the foibles and pitfalls inside military intelligence – a term many have long considered an oxymoron. But the book is deepened with Hill’s research into the actual circumstances surrounding the tunnel spiced with stories from his own time in Berlin as a linguist. “I wanted to record what it was like to fight the Secret Cold war for posterity,” Hill says. “When their children ask ‘What did you do in the Cold War?,’ most Secret Cold War veterans have to say something trite, like ‘If I told you, I’d have to shoot you.’ I wanted to give voice to some of their stories so that they would not disappear when the generations of [characters like my] Kevins and Fast Eddies who are sworn to silence shuffle off this mortal coil.” But this brief description only scratches the surface of what readers will enjoy in Voices Under Berlin. So Spywise has posted two files for readers to get a sense of what the book is all about. First, we asked Hill himself to explain his intentions, techniques, and background in creating this new spy classic. Below is our conversation. Then, Tom generously granted us permission to post one of his later chapters demonstrating his breed of humor. After you check these files out, we have no doubt you too will be wanting more from this very original new voice in spy literature. Q – I get the sense Voices Under Berlin drew from your own time in Berlin, extensive research into its history, and your comic imagination. What were the sources you drew from for the history of the tunnel and the time period during which it was in operation? The lead into this question is quite perceptive.  The story is hung loosely on the historical background of the CIA cross-sector tunnel in Berlin in the mid-1950s, and that came primarily from three sources: (1)Battleground Berlin, a book on the Intelligence war in Berlin written by a former chief of the CIA Base in Berlin in cooperation with a retired KGB Chief of German operations from that period. It has a whole chapter on the tunnel. (2) Spies Beneath Berlin by David Stafford of the University of Edinburgh. (3) The Official CIA history of the tunnel that was prepared in August 1967 and declassified in February 2007. The historical background for occupied Berlin during the tunnel period came from a number of sources such as Berlin Before the Wall by Hsi-Huey Liang and a series of booklets published by Berlin Command for distribution to newcomers. The fact that these army booklets are quite rare and are not to be found in libraries – even in the Library of Congress – made me decide to reprint them as a single volume after I completed Voices Under Berlin. Those interested in the reprint can find it on Amazon.com as Berlin in Early Cold-War Army Booklets. The booklets contain a wealth of background information on occupied Berlin at the time of the tunnel. Very few of the incidents in the book are entirely the product of my comic imagination, though they are all liberally decorated by it, and by my own experiences in Berlin in the mid-1970s. Q – Most sources I’ve read on the Berlin Tunnel focus on British traitor George Blake, who blew the whistle to the Soviets even before the lines had been tapped. Why did you discount this in your novel-historical or literary reasons? The reason that I did not talk about Blake and the persistent legend that the tunnel was used by the KGB for a massive disinformation campaign was historical. Both Battleground Berlin and Spies Beneath Berlin make credible claims that the KGB expressly avoided doing so for fear of compromising Blake. Stafford supports his argument that the Berlin Tunnel was not used for a disinformation counter-intelligence operation by the KGB by pointing to information that came to light during the “Teufelsberg” Conference on Cold-War intelligence operations that brought intelligence professionals from both the CIA and the KGB together in Berlin in 1999. He concludes that “[f]ar from using the tunnel for misinformation and deception, the KGB’s First Chief Directorate had taken a deliberate decision to conceal its existence from the Red Army and GRU, the main users of the cables being tapped. The reason for this extraordinary decision was to protect ‘Diomid’, their rare and brilliant source George Blake.” (p. 180) Stafford ends his discussion of the legitimacy of the material collected from the Berlin Tunnel with a quote from Blake, who was still living in Moscow at the time of the “Teufelsberg” Conference. “I’m sure 99.9% of the information obtained by the SIS and CIA from the tunnel was genuine,” said Blake. (p. 183) Q – While the actual venture was a joint CIA/British Intelligence project, your novel focuses on analysts within the U.S. military. Again, was this inspired from research or an opportunity for you to engage in military humor? Yes, the tunnel was indeed a joint CIA/SIS collection operation. It was known to the Americans as Operation GOLD and to the British as Operation STOPWATCH. According to my historical sources, the Americans dug the horizontal portion of the tunnel, and then the British sent in a team to dig the vertical tunnel up to the cables and make the tap. That division of “labour” is reflected in Voices Under Berlin – though perhaps too subtly – in the chapter “The Calm Before the Storm,” in which the Americans get a month off while the professional miners from Wales dig the vertical shaft, and in the Chapter “The Tap Turns On,” when the chief British technician refuses delivery of the Chief of Base’s implied insult about the tap not being properly installed. My sources point to joint manning of the collection operation, but there is nothing available that talks about the British contribution there. Stafford makes a point of saying how close-mouthed the British are with regard to covert operations, comparing the amount of British info about the tunnel to the amount that has become available from the Americans. Stafford says that when the Russians discovered the tunnel and made it front-page news, the Americans were the ones who got all the limelight of publicity, because Soviet First Secretary Khrushchev was on an official state visit to the U.K. at the time, and was expected at a reception hosted by the Queen in Windsor Castle on the next day. According to Stafford, the British and Soviets agreed to conceal the fact of British participation in the tunnel project so as not to spoil the state visit. This lack of information on the Brits makes the tunnel look almost entirely like an Yank show. I’ve just followed suit. Q – Your book has been compared to the work of Joseph Heller and Richard Hooker. I saw the influence of Heller in the character of the Chief of Station always showing up in his disguises. Did you have these authors, or any others, in mind as you wrote Voices Under Berlin? I was not consciously trying to write like Heller or Hooker, but after the similarity was pointed out to me, I could see the resemblances. I first read Catch-22 shortly after I got out of Army Basic Training and was waiting for my first language course to start in Monterey, California, where the Defense Language Institute is located. The novel made a big impression on me, because I was living in an environment that was full of resonances with the things going on in the book. While the threat of death that Yossarian and his buddies were facing was more immediate than the threat of death that I was under (Monterey, California is, aside from the remote threat of earthquakes, not very hazardous), the Vietnam War was in full swing at that time and all you needed to do to get your orders to an infantry company somewhere in a Vietnamese jungle was to flunk a couple of tests. The threat was real enough to motivate people to study very, very hard. And we had people going crazy – quite literally – from the pressure of the courses. We lived in 40-man open bays in old World-War-II pre-fab barracks, and one morning I woke up to find one of the Russian students in my bay in the fetal position, on top of his wall locker. Whenever anyone came near him to find out what was going on, he said, “I’m a past passive participle. Don’t touch me.” They carried him off while we were in class that morning and nobody ever saw him or heard from him again. I read M*A*S*H at about the same time. The attraction was the same. The story was full of resonances with the life I was leading at the time. In retrospect, the element in M*A*S*H that has perhaps the most resonance with Voices Under Berlin is the reason that Hawkeye, Trapper and [my character] Kevin can get away with being unmilitary. They’re so good at what they do that the military has to put up with them. That fact of life was not apparent to me while I was still in Monterey, because Monterey was not exactly the real army while I was there. It only became clear to me after I was sent off to put what I had learned at Monterey to use. I also found out that the system has ways of dealing with people like that. One of them found its way in to Voices Under Berlin. Q – The level-headed figure in the book is Kevin, and I see your acknowledgments include “Kevin’s daughter.” Which of your characters drew from actual people? The characters in the book are amalgams of people I knew, and people I heard about, and of myself. Prepublication readers of the book who know me, kept pointing to various characters in the book, claiming to have recognized me in them. And they were almost all pointing to different ones. One particularly insightful reader, who worked with me for a long time and was the best man at my wedding, said that he thought it presumptuous of me to write myself into the novel twice. He was right, but not entirely. His count was too low. The personalities in the book are an attempt to paint a picture of generic character types of the people I met (and was) during my career. There is no single individual behind any of them. “Kevin’s daughter” is an astute young lady who is a senior in college. She read the book in manuscript and made some very insightful and useful comments. She’s an Army brat, and her father, like Kevin, is a military linguist. She said that Voices Under Berlin helped her to understand him better. She didn»t want me to give her real name in the acknowledgments, but I wanted to include her, so we compromised, and I called her “Kevin’s daughter.” She knows who she is, and that I appreciated her help. Q – It’s been suggested Kevin wasn’t given a last name or rank to show him as an outsider to military uniformity. Was this your intention? Yes, it was. All the surnames in the book are talking names. A number of them are translations. Some of them are simple plays on words. Sergeant Laufflaecker’s name is based on the German word that means “tread,” as in “tire tread”. “Tread” is the Army slang for someone who has re-enlisted, or been “re-treaded.” Corporal Neumann’s name means “new man” in German. He is the eternal “newk,” the new guy, who doesn’t know how things really work. Blackie’s name takes almost a whole chapter to explain, and Trudy, his girlfriend is a “working girl,” because her name is Russian for “works.” General Molotov’s name is a joke that only becomes apparent when you realize that he always only speaks with Colonel Serpov. The translation of their names is “hammer and sickle.” As Jim Henson of the Muppets once said: “It’s a cheap joke, but we’re worthy of it.” Kevin, however, does not have a last name, which makes him stand out in the Army, where everybody has a last name, first name, middle initial, and a rank to go with them. You have to sew your last name on your uniform “so you won’t forget who you are,” as one wag put it. The Army’s explanation is so that they’ll know what name to put on your tomb stone when they find your body. There’s an old army war story that perhaps explains the place of names and ranks in the military. It seems there was a lieutenant talking to a private who hadn’t quite got a handle on the finer points of military courtesy. The private says, “My name’s John. What’s yours?” The lieutenant replies, “You can call me by my first name too. It’s lieutenant.” It sounds a lot funnier if you’ve never met someone whose first name was lieutenant. I, however, have. Not having a last name or a rank is intended to mark Kevin as a civilian in uniform. Sergeant Laufflaecker calls Kevin “Kilroy” as a joke. It’s not really Kevin’s surname. Kilroy was the nickname (and graffiti tag) associated with the average American GI during World War II. Kilroy was everybody and he was nobody, all rolled into one. The suggestion of Laufflaecker calling Kevin “Kilroy” is that Kevin represents the countless Monterey Marys [graduates of the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California] who fought the Secret Cold War for one tour and then went home to do other things. They never became “soldiers,” and didn’t care about rank or position, just like Hawkeye and Trapper in M*A*S*H*. The only thing that mattered to them was professional competence, and the bureaucracy was often at pains to understand people like that. The other character who has no surname is the Chief of Base. He is nameless, because the secrecy of his job requires him to be so. He is like Peter Sellers, who once said, “I can play anyone, but I can’t be myself. There is no me. There used to be one, but I had it surgically removed.” These two nameless characters – the Chief of Base and Kevin – are the antipodes of the story, the older man showing what the younger one could develop into, if he stayed in the business long enough. Q – The use of Kevin’s translated transcripts of the Russians’ telephone calls allows readers to see inside the Russian perspective. At the same time, the transcripts allow us to see Kevin’s abilities as both a translator and analyst. How did you come to use this device? This approach is drawn from real life. Its goal is not only to present the reader with the Russian perspective, but to help the reader understand Kevin’s ear-centric view of the world. The Chief of Base’s disguises, for example, never fooled Kevin for long, because Kevin could recognize his voice. Courses on instructional technique break students down into “aural learners” and “visual learners” based on the differences in their learning styles, and teachers are encouraged to vary their presentations to take this into account. To some extent this categorization explains why some people (Kevin) make good transcribers and others (Fast Eddie) don’t. Books are, in general, a very visual medium, and by writing an “aural” book, I wanted to push the reader out of his/her “visual” comfort zone to give them a better feeling for what it is like to be ear-centric, because if you are going to understand what makes Kevin tick, you need to look at the world through his ears. Q – Once the phone taps begin operation, Voices Under Berlin becomes a very episodic book with a series of pranks, missteps, and all manner of scenes full of muddled military thinking. What of these came from experience, what from your sense of humor? Some parts of the book are cut from the same bolt of cloth as the Emperor’s new clothes, but most of the episodes in the book have some basis in fact, or personal experience. The delivery of the “facts” is what is based on my sense of humor. The flood that stopped digging on the eighth of September 1954 is factual, as is the snow almost giving away the location of the tunnel later that winter. The episode about the courier run to Gatow, for example, s based on one paragraph in Battleground Berlin (p. 423) about a problem with the chief of the classified shipment registry section of Berlin Base. Magnetic tape is very heavy. I know this for a fact. I’ve lifted more than my share of boxes full of it. The tunnel operation was producing a great deal of tape that had to be shipped out for processing, and the chief of registry began complaining about all the heavy boxes he had to ship. He had no need to know that the boxes were full of magnetic tape from the tunnel cable tap, so they told him that the boxes were full of uranium ore from the East German Wismut uranium mines. Targeting the Wismut mines was an operation that was a more or less open secret among those assigned to Berlin Base, and they felt safer telling him that than telling him what was really in the boxes. The scene’s elaboration is from my sense of humor. The part of the chapter about the lieutenant waving around his sidearm with three corroded rounds in the magazine is from personal experience. It makes for a great war story today, but at the time I didn’t think it was so funny. Q – What points, what themes were you trying to illustrate with Voices Under Berlin? An operation like the Berlin tunnel can only succeed if there are people like Kevin to work it. This fact, however, seems to escape the attention of some of the people who “manage” linguists, because they are unable to understand how linguists think. Turning disembodied voices into the kind of intelligence that can sink one of those proverbial ships of World War II poster fame is harder than it looks. This theme, as developed in Voices Under Berlin, is very similar to the central theme in Ayn Ran’s Atlas Shrugged. It looks at what happens when the people whose little grey cells make things work become disillusioned with the system and leave, or are banished from it. Another goal was to write a spyfi novel based on the reality of espionage. That’s not to say that I am not a fan of Ian Fleming, Robert Ludlum or Le Carré. I’ve read all their books, and it’s all Ian Fleming’s fault that I was in ASA [the Army Security Agency]. That, however, is not reality. It’s fantasy. Real-life spying is a far cry from the action-packed screen adventures of spies like James Bond, liberally decorated with dazzlingly attractive fold-out girls. In the movie Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), Bond is seen in Oxford, brushing up his Danish under the tutelage of a voluptuous instructor in a state of undress. When Miss Moneypenny gets Bond on the phone and discovers what he’s doing, she calls him a “cunning linguist.” Military linguists have been calling themselves “cunning linguists” since long before Miss Moneypenny made the term popular in that movie. I’ll bet that one of the script writers must have been a military linguist “in another life.” I’m a three-time graduate of the Defense Language Institute, and none of my language instructors ever looked like that, and we never did any role-playing with the set of vocabulary that Bond was practicing in the movie. Q – Did anyone ever encourage you to include more Bondian elements in your book? When the manuscript for Voices Under Berlin was making its way around literary agents in search of someone to represent it, one agent said that the book was very Helleresque, but that it would sell better with more sex and violence. That wasn’t, however, the book that I wanted to write. I wanted to write a book that was based on the reality of the mind numbing boredom of a Sunday mid while you’re waiting for the target’s loose lips to sink a ship. I wanted to record what it was like to fight the Secret Cold war for posterity. When their children ask, “What did you do in the Cold War?,” most Secret Cold War veterans, have to say something trite, like “If I told you, I’d have to shoot you.” I wanted to give voice to some of their stories so that they would not disappear when the generations of Kevins and Fast Eddies who are sworn to silence shuffle off this mortal coil. Voices Under Berlin may not be exactly the story that each and every one of them would like to tell, but it is close enough so that people who fought the Secret Cold War in places other than Berlin say that they felt right at home while reading it. I wanted Secret Cold War vets to be able to answer their children and grandchildren with: “I can’t tell you exactly, but why don't you read Voices Under Berlin?” And I wanted to entertain people with what I was writing. Q – What projects are you working on now? I have a new novel entitled The Day Before the Wall. It is based on a Berlin legend that we knew that the wall was going to be built, and we knew that the East Germans had been instructed to pull back, if we took aggressive action to stop construction. The novel follows an American sergeant who has this information and is trying to cross back to the west with it while it is still relevant. His return “home” is made more difficult by the fact that the Stasi have framed him for the murder of his post-mistress, and have asked the West-Berlin police for help in tracking him down. The key question of the novel is that even if he does get back to report what he knows, will the Americans believe him and take action on it? The key question of getting it published is can I get prepublication clearance for the manuscript? To learn more about Voices Under Berlin, check out the book’s website – Voices Under Berlin. A sample chapter of Voices Under Berlin can be found in the Spies in History & Literature section of this website. Voices Under Berlin was among the winners of the July 2008 Hollywood Book Festival. Wikipedia has an article about the Hollywood Book Festival. T.H.E. Hill’s Voices Under Berlin and his other books are available in bookstores everywhere, as well as these online merchants ~

Amazon U.S.

|