HOMEWesley Britton’s Books,

|

Spies on FilmSpies on Television & RadioSpies in History & LiteratureThe James Bond Files |

|

Spies on Film ~ From Madman to Icon

– A Spy-ography of Peter Lorre

By Wesley Britton

The mysterious Peter Lorre (1904-1964). According to a May 1936 article by Jean Straker for Film Pictorial, a weekly British publication, Peter Lorre’s early persona on and off screen was a study in type-casting. For example, Straker recounted one evening when Lorre strolled in Berlin, suddenly hearing a woman scream. “It’s him! There! THE MURDERER!” In Straker’s words, she grabbed the hand of a young girl and hurried away. Other men and women looked and cringed. What they saw was the famous child killer of the film M, a movie that was something of a sensation in Europe that year. According to the article, Lorre then sadly spoke to a friend as they passed a cafe. “Let’s go inside. It is terrible, Emil. They all recognize me.” “That is fame,” was the alleged reply. “You are famous and they pay tribute to your artistry.” “Look, it is not me they see,” retorted Lorre. “It is the murderer. I am not famous. It is the murderer. Emil, they think I am a murderer. It is impossible. I will be chased from the streets. Do you think that if I were to play a different character – perhaps comedy – the public will forget the murderer?” (Note 1) No, as it turned out. But the legacy of Peter Lorre expanded greatly over the following decades. On screen, yes, he remained a colorful villain, but he was also an affable sidekick, an action hero of sorts, and, yes, a memorable actor in comic roles. And he was an important figure in the history of spy films. A European Star Born June 26, 1904, as Laszlo Loewenstein (a.k.a. Ladislav Loewenstein) in Rosenburg, Hungary, Peter Lorre grew up in Europe and spent his early acting career on stages in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. He worked in his first film in 1929, and his first success was playing in director Fritz Lang’s M (1931), the role that made him famous as a screen monster. (Note 2)

Leslie Banks, Peter Lorre, and director Alfred Hitchcock on the set of The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934). For years afterward, Lorre was most often cast in roles calling for varying degrees of madness as Hollywood executives wanted him to repeat his signature role in M, the sinister/criminal/psycho killer of children. After leaving Germany when the Nazis came to power in 1933, Lorre began his work in espionage capers when he met with director Alfred Hitchcock in England. As it happened, Hitchcock’s long interest in spy stories first came to the screen in the original The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), an assassination plot based on then-popular Bulldog Drummond stories. For this project, Hitchcock cast the émigré actor despite the fact Lorre had a minimal command of English and had to learn his part phonetically. Regarding this film, Stephen Youngkin, James Bigwood, and Raymond Cabana, Jr. noted –

Two years later, Hitchcock cast Lorre again as “the General” in Secret Agent, a movie very loosely based on the spy stories of W. Somerset Maugham. Thus, Lorre was there when many templates in the film spy genre were created. For example, Secret Agent was a precursor to many spy films of the future, featuring a Swiss mountain setting, a train chase, and casino scenes as the hero and heroine (Sir John Gielgud, Madeline Carroll) chased a Nazi to Constantinople. “Critically panned as a whole, the film was praised for Lorre’s understated portrayal showing the duality of human nature, a mix of innocence and malevolence, his trademark.” (Youngkin 94) Wanting to change his image, Lorre signed to a 20th Century-Fox contract in 1936. He asked for and received a chance to play a leading man, at least in “B” pictures. He starred in eight installments of the very popular Mr. Moto series, playing a polite judo-expert Japanese detective. This series had several connections to fictional spycraft. In the original J.P. Marquand novels, Moto was a secret agent working for the Japanese government in the Pacific Rim. But the films changed him into a freelance detective to imitate the equally popular Charlie Chan character. Still, detective Moto was occasionally pulled into covert investigations. In Mr. Moto Takes a Chance (1938), the story was a pre-WW II adventure with Japanese and British intelligence working together. Critics laughed at the number of spills tossed into a movie less than 70 minutes long, including trap doors, poison air guns, machine guns, bowler knives, carrier pigeons, and terrors from jungle beasts. Not to mention an Amelia Earhart-type heroine who falls from the skies while on an around-the-world flight. Of course, she’s the British spy.

Lorre starred in the popular Mr. Moto film series. In the same year, Mysterious Mr. Motohad a quasi-espionage storyline. A group of gangsters called the League of Assassins tried to steal an industrialist»s formula, presumably to sell for nefarious purposes. Moto (calling himself Agent 673 of the International Police) teamed with the British CID. Mr. Moto’s Last Warning (1939) was about a plot to start a war between France and England by an unidentified third party who schemed to blow up part of the French fleet. One indication of the series’ popularity was a practical joke played on Lorre during filming of the Moto series. According to The Films of Peter Lorre, someone replaced Lorre’s identification with a card reading, “Mr. Moto, Japanese Spy.” Pulled over for speeding, Lorre unintentionally showed the policeman this card. Fortunately, the officer was a fan and let the actor go (42). (Note 4) During this period and beyond, Lorre was given a variety of roles on both film and radio requiring a pronounced European accent. During the years leading up to and including World War II, such roles usually meant playing on the losing side of the script. For example, Lorre played a German major in Lancer Spy (1937). In this script, he loses to George Sanders. who played a British naval officer posing as a German baron. Dolores Del Rio was the German Mata Hari figure working for Sig Rumann, who played Lorre’s commanding officer. Del Rio’s task was to meet Sanders and determine if he was really the German officer (Baron von Rohbach) escaped from his captives or a look-alike. Falling in love with him, she uncovered his true identity and helped him escape from Germany. In eMail (June 2005) to this author from long-time Lorre fan Cheryl Morris, “Originally, Lorre was set to play the lead role. But at 20th Century-Fox, Peter was not a leading man. Where he played the lead, as in the Mr. Moto series, the films were considered ‘B’ pictures. Darryl F. Zanuck, the studio head, decided to give Lancer Spy a larger budget – and that meant Peter could not star. One day before production was scheduled to begin, Lancer Spy was yanked, and the script re-written.” In the final version, Lorre ended up with little screen time. More successfully, Lorre was the master spy Baron Rudolf Maximilian Taggart in Crack-Up (1937). His Taggart pretended to be Col. Gimpy, a harmless, gentle, bugle-blowing nitwit. He’s out to steal the secrets of a new plane, The Wild Goose. Critics found this a strange film as no character was heroic. (The cast included Brian Donlevy as a double-crossing pilot; Donlevy went on to star as American agent Steve Mitchell in both the TV and radio versions of Dangerous Assignment.) In the view of Anne Sharp, Lorre’s Taggart was in many ways a reprise of his portrayal as Abbott in The Man Who Knew Too Much. (Note 5) According to Cheryl Morris, “Peter wanted to play comedy, and casting him as a villain who poses as a nitwit was 20th Century-Fox’s way of giving Peter what he wanted and getting what they wanted out of him, in the way of a villain.” As one contemporary review put it –

Success in the War Years Then, Lorre’s career took an upswing when he first teamed with actor Sydney Greenstreet in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and appeared in top-notch efforts like Casablanca (1942). While debates continue over whether or not this classic can be considered a spy film, many have noted that the characters of Major Strasser (Conrad Veidt) and Ilsa Lund Laszlo (Ingrid Bergman) come to Humphrey Bogart’s Rick’s Café seeking letters of transit signed by General Weygand. Rick had obtained these from Ugarte (Lorre) before his arrest by the Vichy police. Along with Ilsa came Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreied), a Resistance fighter who’s escaped from a concentration camp. No one is a spy per se, but the action of seeking secret papers and plotting an underground escape are typical elements in espionage-oriented scripts.

Jimmy Durante entertains the cast of All Through the Night – Kaaren Verne, Humphrey Bogart, Peter Lorre, and William Demarest. Also in 1942, Lorre worked with Conrad Veidt and Humphrey Bogart again in All Through the Night. Veidt was a German spymaster and Lorre was Pepi, a nightclub piano player and the Nazi gang’s assassin, in director Vincent Sherman”s comedy starring Bogart as “Gloves” Donahue. In this story, “Gloves” stumbled across a Nazi “Fifth Column” group in New York in a yarn filled with chase scenes. The final climax had Donahue leading an army of his pals (including Jackie Gleason and Phil Silvers), fellow gamblers, and friends of rival nightclub owner Marty Callahan (Barton MacLane) to stop a motorboat loaded with explosives planned to destroy a U.S. battleship. Lorre’s work with Sydney Greenstreet during these years became known as the “Little Pete-Big Syd” pairing in films ranging from considerable interaction between Greenstreet and Lorre to both being cast in films without much screen time together. (Note 6) Lorre was Greenstreet’s adversary in Background to Danger (1943) in which a Nazi agent (Greenstreet) forged maps hoping to ferment a panic in Turkey. Sometimes described as a “Casablanca clone,” this was a movie of special interest as it was based on an Eric Ambler novel, Lorre playing Ambler’s Nikolai Zaleshoff. Some critics say the book was turned into World War II propaganda with bombs and stunts superseding the script. Others believe the script kept close to the spirit of Ambler’s novel with minimal changes in locale. (Note 7) The Conspirators (1944), another WWII spy yarn, featured Greenstreet and Lorre again in a story where a Dutch freedom fighter escaped Nazis and went to Lisbon where he worked with an underground cell. In a story of cross and double-cross, Hugo Von Mohr (Victor Francen), married to Irene (Hedy Lamarr), was an official of the German legation and a member of a spy ring run by Riccardo Quintanilla (Sydney Greenstreet). Greenstreet thinks Francen is on his side, but he’s the traitor in their midst and betrays them to the Nazis during a game of roulette. Peter Lorre played Jan Bernazsky and Paul Henreid was Vincent Van der Lyn. The film was damned by critics of the era as confusing – a Nazi playing an Ally playing a Nazi. On a much higher plane, Lorre and Greenstreet returned to Balkan settings in another film based on an Eric Ambler book, The Mask of Dimitrios (1944). The film’s director, Jean Negulesco, thought Lorre was the finest actor in Hollywood and wanted to cast only character actors because he respected them more than stars. In a studio power play, as Jack Warner hated Lorre, he arranged that the actor wasn’t given star billing. (Note 8) In Hal Erickson’s view, in this film “the diminutive actor gave one of his finest and subtlest performances.” (Note 9) Lorre fan “Nancy Simpanda” agrees, saying –

In his next spy project, Lorre played with Charles Boyer and Lauren Bacall in Confidential Agent (1945), a dark look into espionage in a script based on a more humorous early Graham Greene novel. In the story, Boyer was an idealistic, amateur agent for the anti-Fascist Spanish rebellion sent to England to either secure delivery of coal or block it from getting to the government. A series of sad mishaps, and traitors within his own group including Lorre, lead to tragic events but ultimately he succeeded in stopping the delivery. Bacall, panned by critics, in the spirit of Hitchcock’s 39 Steps, played the world-weary cynic who helped him. But not all Lorre’s spy films of the era were built on such literary bases. In 1940, Lorre was the villain again in another imaginative story, Island of Doomed Men. Robert Wilcox played Agent 64, using the assumed name John Smith. Working for an unspecified and clearly covert agency, he’s assigned to find out what’s going on at a strange island run by Stephen Danel (Lorre). Lorre’s low-key, menacing Danel was using parolees to dig diamonds in a white slavery scheme. In 1942, Lorre played a baron in Invisible Agent, a precursor to many spy projects blending science-fiction with espionage. In the movie, another WWII propaganda picture, Lorre’s character was a Japanese agent who's trying to shake down the grandson of the Invisible Man for his invisibility serum. Meanwhile, the grandson parachuted behind German lines to steal a spy list in Berlin. (The film co-starred sultry-voiced Hungarian actress Ilona Massey, later the star of radio’s Top Secret.) Post-War Movies As World War II wore down and the Cold War heated up, Lorre was there when the first signs of McCarthyism began to show themselves. On the HUAC watch-list because of his friendship with Bertolt Brecht, Lorre would likely have been called to testify had he not left the country. (Note 11) Then, in 1951, Lorre returned to Germany, where he directed, co-wrote, and starred in Der Verlorene (The Lost One), the most significant espionage-related film Lorre ever made. “It is a beautifully made film,” Anne Sharp believes, “and a very important one. It was one of the first films made in Germany after World War II about the Nazi era. Considering that it was made by a Jew who had suffered directly as a result of the Shoah, it is all the more remarkable.” (Note 12) Taking the storyline from a newspaper article, Lorre sketched out a screenplay, preferring to improvise most of the dialogue during production. (Note 13)

Lorre directed, co-wrote, co-produced, and starred in Der Verlorene (The Lost One, 1951). As this film has been seen by few English-language audiences, a detailed synopsis seems worthwhile here. In the story, Lorre played Dr. Karl Rothe, a research scientist working on a bacteriological serum for the German government. Government spy Hoesch (Karl John) has been assigned to supervise Rothe’s work, and has an affair with Rothe’s fiancée, Inge (Renate Mannhardt). He learned Inge was passing information about Rothe’s research to her father, an Allied spy. Hoesch and his supervisor, Colonel Winkler (Helmut Rudolph) then deliberately humiliate Rothe by telling him every detail of Inge’s betrayal of him. Frenzied with anger, Rothe murders Inge, but Hoesch and Winkler cover up Rothe’s crime and force him to go on with his work for the Nazi government as though nothing has happened. Under the stress of his unresolved anger and guilt, Rothe murders another woman who reminds him of Inge. He then steals Hoesch’s gun and plans to murder Hoesch and Winkler. But, at Winkler’s house, he discovers that Winkler himself is involved in a plot to betray the Nazi government as Allied forces are about to overtake Germany and he wants to save his skin. At film’s end, Rothe meets Hoesch after the war at a refugee camp and takes his final revenge.

But not all his films of the era were so serious. In the Fred Astaire, Cyd Charisse musical, Silk Stockings (1957), (1957), Lorre atypically played a Commie commissar singing Cole Porter songs while being seduced by the comforts of the West. During the 1950s, Lorre became heavier and his roles were more frequently in “B” movie projects. He also began his career as an actor in television dramas. The most notable for spy fans was his battling Barry Nelson’s James Bond in the CBS October 21, 1954 Climax! adaptation of Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale. As Bond expert Lee Pfeiffer noted in his introduction to the “Collector’s Edition” video version of the film (which included footage of Lorre’s character’s death which was thought long lost), the choice of Barry Nelson as an Americanized “card-sense Jimmy Bond” was less successful than the casting of Lorre as the ruthless, razor-carrying Russian agent, “Le Chiffre”. In a March 2001 interview with Barry Nelson, Pfeiffer learned the American actor might not have been the first screen 007 if not for Peter Lorre. At first, Nelson was no longer interested in dealing with the constraints of live TV, was out relaxing on one of those great Jamaica vacations we all wish to be on. It was then that his agent called about the part, and James Bond wasn’t yet a known commodity. He could put his vacation on hiatus and visit Jamaica or somewhere else like Cancun, Mexico, again later on. “The main purpose he reconsidered,” Pfeiffer says, “was simply to have the opportunity to work with Peter Lorre. Nelson had been a great admirer of his work and felt he might never get the opportunity to meet with him again.” On the set, Nelson “felt the character of Bond was too ill-defined and had no distinct personality. He argued that Bond’s dialogue be improved and Lorre backed him up, thus certain changes were made.” While Nelson said he impressed Lorre by screening some of Lorre’s German films during the down time of the production, it’s doubtful anyone in the U.S. had access to material then held only in East German vaults. (Note 14) Thus, Lorre was the first evil adversary to utter such phrases as, “He’s lucky, your Mr. Bond.” Later, Lorre did one guest appearance on the NBC television spy drama, Five Fingers, in the episode “Thin Ice” on December 19, 1959. This show, too, had Bond connections. Its lead, David Hedison, went on to be the only actor to play 007 buddy Felix Leiter in two films, Live and Let Die and License to Kill. Ironically, this episode had connections with another Lorre TV appearance. In 1951, L.C. Moyzisch’s book, Operation Cicero (1950), was adapted as a film, Five Fingers, starring James Mason which was turned into the Hedison series. Then, Lorre appeared in the 20th Century-Fox Hour TV drama, “Operation: Cicero” (broadcast CBS, Dec. 26, 1956) as Moyzisch. The TV episode also featured Ricardo Montalban and Maria Riva. Legacy Peter Lorre died March 23, 1964, from a stroke. Long before his death, his famous face and voice had become the stuff of parody in Warner Brothers cartoons and commercials. Charles Addams said he based the character of Gomez Addams on Lorre. One obvious take-off of the Greenstreet/Lorre characters in The Maltese Falcon appeared in a 1968 episode of The Avengers, “Legacy of Death.” (Note 15) One caricature of Lorre’s image was in a Bozo the Clown cartoon called “Slippery Sly, International Spy.”

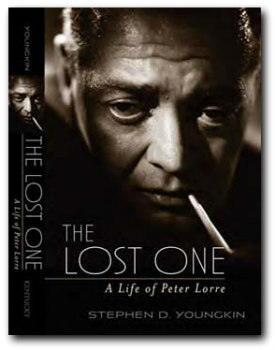

The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre, by Stephen D. Youngkin (University Press of Kentucky, 2005). But Peter Lorre was a man who’d also earned considerable respect over the years. Lorre has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and in 2004, his centenary year, the Austrian Film Museum had a month-long retrospective of his career in which they showed many of his film and TV performances. His reputation remains very high in Europe and among serious theater people in the U.S., in no small part because he worked with playwright Bertolt Brecht. In 2005, the first full-length biography of Lorre, The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre, written by Stephen D. Youngkin, was published through University Press of Kentucky. Without question, Peter Lorre is an important figure in entertainment as an actor, a personality that transcended the characters he played, and his presence in motion picture history. For many, he’d become known more for comedy than the killer in M that had frightened German mothers. For example, according to Hal Erickson, “Lorre employed his familiar repertoire of wide eyes, toothy grin, and nasal voice to invoke laughs rather than shudders.” Anne Sharp says of him, “Small, almost childlike at times, with huge, heavy-lidded eyes and haunting Viennese-accented voice, Lorre projected an aura of decadent menace when playing a villain. At the same time, his puckish sense of humor made him just as effective in comic roles.” But beyond his acting roles and the endless exploitation of his accent and mannerisms, Peter Lorre has left an important legacy for enthusiasts of spy films. Again, in the words of Anne Sharp ~

And, according to Sharp, Peter Lorre’s place in film history links with contemporary concerns about the roles of ethnic backgrounds on the large screen. Sharp believes ~

So Peter Lorre still entertains us and is the subject of provoking reflections on the nature of evil, or on a more focused level, our perceptions of who the enemy is during times of conflict. His films are still worth seeing, enjoying, and perhaps some time pondering over how Hollywood shapes our views of opponents from World War II, the Cold War, and beyond. Notes ~ Note 1 – Straker, Jean. “Such a Modest ‘Murderer’” – Peter Lorre, star of Crime and Punishment, may make you shudder when you see him on the screen, but in private life he is so shy that he is afraid of strangers.” Film Pictorial. May 9, 1936. Note 2 – Judging from one review of the DVD version of M, the film still has resonance. According to the (rather nasty) reviewer for the New York Press –

While Lorre wasn’t yet a film spy in his early European films, there is industrial espionage involved in one German film, F.P. 1 Antwortet Nicht (1932). And also see the “Spy-ography” of Fritz Lang, posted in the Spies on Film section of this website. Note 3 – See Youngkin, Stephen, James Bigwood, and Raymond Cabana, Jr. The Films of Peter Lorre. Citadel Press, NJ, 1982, page 33. The film is discussed on pages 33-34, 85-86. Secret Agent is discussed on 37, 94-95. For very detailed looks into the spy films of Alfred Hitchcock, see my Beyond Bond: Spies in Film and Fiction (Praeger Publishers, 2005). Note 4 – In 1965, The Return of Mr. Moto was a low-budget attempt to bring back the character. This time around, Henry Silva was Interpol agent Moto investigating insurance fraud and possible enemy agents tampering with oil fields. Co-starred Sue Lloyd. Note 5 – Anne Sharp was list moderator for the Peter Lorre Yahoo list group. The group’s website had a number of useful files. In fact, this article owes much to many members of that group, and I here give them all a very hearty bow of gratitude. Note 6 – According to Cheryl Morris, “Peter called them the ‘Abbott and Costello’ of mystery. I’ve seen them billed as ‘The Fat Man of Mystery’ and ‘The Little Man of Mystery.’ They were in 9 films together. They had a screen image that was apparently based on their pairing in The Maltese Falcon, and the only time they re-enacted that was in Hollywood Canteen (1944), where Peter and Sydney wrote their own bit for the film. In the remaining seven films, their relationship varied from friends, to enemies, to uneasy allies.” Note 7 – Among the differences between novel and film, in Cheryl Morris’ words – “In the novel, the Greenstreet character and the Lorre character are each trying to get the forged maps. Sydney’s character is to receive them from a traitor in Peter’s organization. While on a train to meet Sydney in Linz, the traitor turns over the maps to a journalist named Kenton, and when the traitor is killed, Kenton suddenly finds himself in the middle of this situation, with both sides after him and the maps. “In the movie, the journalist Kenton is changed to an American agent named Barton (played by George Raft), whose job is to find out how Germany plans to create an ‘incident' in Ankara, Turkey. Raft becomes Sydney Greenstreet’s adversary, and Peter’s role in the story is drastically reduced in importance.” Note 8 – Jack Warner disliked Lorre because Peter wouldn’t sign an exclusive contract with the studio. He wanted to do two films outside the studio every year, and he wanted to do radio. Warner Bros. was accustomed to “owning” actors, body and soul. Note 9 – Hal Erickson’s short overview of Lorre is posted on-line at the AllMovie website. Note 10 – “Nancy Simpanda” was a distinguished contributor to the now-closed Peter Lorre list on Yahoo groups. She pointed to several of the sources mentioned here. An adaptation of The Mask of Dimitrios (April 16, 1945) was among the programs for which Lorre starred for the Screen Guild Theatre on radio, again with Sydney Greenstreet. Note 11 – According to The Films of Peter Lorre, “. . . soon two agents from the FBI called on Lorre. They produced a list of names and asked him if he knew the people. With ‘the face of a cherub who couldn’t possibly tell a lie,” as a friend characterized Lorre’s comic delivery, Peter began rattling off the names of everyone he knew. ‘If you want to know who I know, you had better have more names,’ he added politely.” (Page 50) For those interested in FBI surveillance of Lorre during the McCarthy era, see the official website of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. There are links to Hoover’s snooping into the lives of many other celebrities posted at this site. Note 12 – Peter Lorre’s family knew much about Nazi persecution of the Jews. Lorre’s wartime radio performances put his family in dire jeopardy. As described in The Lost One ~

Note 13 – According to the Lorre biography, The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre, “A small note in Film Press, August 15, 1951, reported that [Egon] Jameson was writing a sequel novelization of Der Verlorene, based on the film script, for the Münchner Illustrierte. Clearly inspired by the original concept of Das Untier, the serialized story reinforced rumors that Lorre had indeed reached into the past for the pathological roots of the film. Egon Jameson incorporated dialogue taken verbatim from the Schroedter script, indicating that either he contributed to the early development of the screenplay or had a free hand to plagiarize lines that were eliminated during the evolution of the story.” In 1996, Belleville Verlag [Munich] published a trade edition of the serialized story and credited Lorre as author, again at Egon Jameson’s expense. Note 14 – The interview with Barry Nelson was intended to become a commentary track for a projected “Special Edition” DVD release of Casino Royale. But when EON Productions bought the rights, the project was dropped, and this interview may never be released. The notes here are from Lee Pfeiffer’s memory of this taping and are not from the video itself. For Bond fans, I provide here a few other items Lee sent me from his memories of the discussion: “Nelson was unaware that Bond was supposed to be English. On the set, Nelson was well aware of the fact that the live production greatly restricted the action to only a couple of sets. . . Nelson considers his brief stint as James Bond as a curious but unremarkable chapter in his long career. He has not followed the Bond series with any particular sense of interest over the years, though he does concede that Sean Connery is probably the definitive actor to portray the character.” In addition, Lee remembers Nelson saying he wanted to work both with Lorre and Linda Christian, a friend of his from MGM contract days. For more details about the Climax! “Casino Royale” and the TV version of Five Fingers, see my book Spy Television (Praeger, 2004). Note 15 – For more details about the Avengers episode, see the website The Avengers Forever. Stephen D. Youngkin’s biography of Peter Lorre, The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre, is available in bookstores everywhere and these on-line merchants ~

Amazon U.S.

For more information on The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre, please visit the book’s official website. Photographs and images courtesy of Stephen D. Youngkin. |