HOMEWesley Britton’s Books,

|

Spies on FilmSpies on Television & RadioSpies in History & LiteratureThe James Bond Files |

|

Spies in History & Literature ~ British “Insider”

Spy Fiction in the Twenty-First Century – Dame Stella

Rimington’s Novels

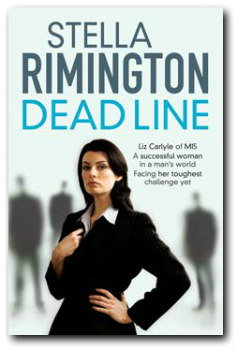

By Mark T. Hooker

Dame Stella Rimington, British spy author Dame Stella Rimington (1935- ) is the former (1992-1996) Director General of the British domestic intelligence service MI-5. Now retired from public service, she has taken up the writing of spy novels, and currently has four novels to her credit – At Risk (2004), Secret Asset (2006), Illegal Action (2007) and Dead Line (2008). A fifth novel is in preparation. She is hardly the first British intelligence officer to turn author. Her literary-intelligence-officer predecessors include such well-known spy-fiction authors as Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, Ian Fleming, John le Carré and Ian Mackintosh. (Note 1) Twenty-first-century insider spy fiction has taken a turn away from James Bond and toward a higher proportion of realism added to the fiction mix. Rimington is a part of this sub-genre of more realistic spy fiction written by insiders, which has more American author-spies than British ones. American novels of this type are represented by works like – The Dream Merchant of Lisbon by Gene Coyle (2004), Edge of Allegiance by Thomas F. Murphy (2005), A Train to Potevka by Mike Ramsdell (2005), and Voices Under Berlin by T.H.E. Hill (2008). (Note 2) In his paper “Spy Fiction, Spy Reality,” (Note 3) written to justify the teaching of a course on spy fiction at The National Defense Intelligence College (NDIC), (Note 4) Jon A. Wiant, who holds the Department of State Chair at the NDIC, says that one of the four compelling reasons for reading spy fiction is that “at its best the literature gives us a window into the organizational pathologies that complicate the lives of the modern intelligence officer” (p. 115). MI-5 vs. MI-6 In American twenty-first-century insider spy fiction, the organizational pathology most often seen is conflict between the bureaucrats at headquarters in Washington and the case officers in the field. (Note 5) In Dame Stella’s novels, the organizational pathology that stands head and shoulders above all others is the conflict between MI-5 and MI-6, roughly the British equivalents of the FBI and the CIA. In At Risk, she notes that “for all the supposed new spirit of cooperation [that arose after 9/11 (Note 6)], Five and Six would never be serene bedfellows” (AR p. 47). James Bond James Bond is the best known literary MI-6 officer in the world, and Dame Stella takes him on in an article she wrote for TheStar.com. (Note 7) There she says that Liz Carlyle whose “intellect, intuition and professional skills” combine to counter the security threats of today is “the antithesis of James Bond”.  Dame Stella reasserts this point in her first book (At Risk) with the description of the kind of car that Liz drives. Liz Carlyle’s car is a second-hand Audi Quattro with a CD player “on the blink” (AR p. 92) and no air-conditioning (DL p. 94), while Bond’s Aston Martin DB5 was named the most iconic British car of all time, in a poll in October 2008. (Note 8) In 2006, a DB5 that was used in one of the Bond movies was sold for $2,090,000 at auction in Arizona. (Note 9) Liz’s car is hardly in the same class. Any fan of the Bond books and movies would find it impossible to imagine Bond without a weapon. There is an extensive Wikipedia page, the only content of which is a list and discussion of James Bond’s firearms. (Note 10) Liz Carlyle, however, is never armed. In At Risk, Liz says, “We”re just an intelligence gathering organization, after all. We don’t do violence” (p. 105). In The Dream Merchant of Lisbon, one of the wave of new American insider spy novels, Coyle’s hero Shawn Reilly comes in to his embassy office during lunch so that he will not be disturbed while he catches “up on his financial accountings and other non-glamorous administrative aspects of being an intel officer.” The narrator quips that Reilly had “seen every James Bond movie ever made and never once had [Bond] ever had to file an accounting.” (p. 254) In Dame Stella’s novels, her heroine Liz Carlyle, a thirty-something MI-5 officer, seemingly does not have to file accountings, but when she returns from a “pleasant, tranquil, and agonizingly uneventful” (p. 4) convalescent leave at the beginning of Secret Asset, Liz is rescued from the “mountain of paperwork, which had accumulated during her absence” by an urgent request for a meeting by an asset she had recruited. (SA p. 5) Realistically enough, this is not the only thing that gets between Liz and the “sharp end of operations,” which is the part of her job she relishes. (SA p. 4) She has to deal with a number of commonplace personal problems like coming in to the office late “courtesy of the bloody Northern Line” of London’s Underground railway system (AR p. 9), a malfunctioning washing machine (AR p. 7), a wonky central heating unit (AR p. 31), her mother’s “well-intentioned homily about meeting someone nice” (AR p. 6), and her mother’s illness (SA). As Max says in the movie Notting Hill (1999), “James Bond never has to put up with this sort of shit.” (Note 11) Despite the anti-matter images of Bond above, Dame Stella’s novels have a number of resonances with Fleming’s work. In Illegal Action, Dame Stella’s description of the training that her Russian illegal went through has a resonance with Fleming’s description of the training the Soviets gave to Donovan Grant, code-name “Granit”, in From Russia with Love. (Note 12) Dame Stella does, however, change the gender of her illegal which makes her character seem more like Rosa Klebb. Twice a year during his training, on the night of the full moon, Grant was taken “to one of the Moscow jails,” where “he was allowed to carry out executions with various weapons – the rope, the axe, the sub-machine gun” (FRwL p. 23). The illegal in Dame Stella’s story had also been allowed to kill in training. “They took convicts out of the prisons – those who had been sentenced to death – and put the trainees up against them. . . it was a fight to the death. She had been determined that whoever died, it would not be her.” (IA p. 88) In At Risk, a bomb has been planted in the car belonging to the target’s stepson. The reason that the bomb does not go off in the proximity of the target recalls Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger (1959), in which Pussy Galore replaces the nerve gas to be dispersed in aerosol form over Fort Knox with a harmless substance because Bond has awakened something in her. In At Risk, Lucy changes her mind and removes the bomb from the boot of the car before the car can be driven to the target’s home by his stepson, because the stepson has awakened something in her. Dame Stella’s novels also display a number of overt allusions to the Bond canon. In At Risk, one of the MI-6 officers with whom Liz interacts claims – somewhat tongue in cheek – that he joined the service because he always had a “Moneypenny complex” about all the “glamorous Foreign Office secretaries” (AR p. 53). He’s so obnoxiously “rather pleased with himself” that Liz’s office mate suggests that she’ll “have to kill him. Kick him in the ankle with your pointy shoe, Rosa Klebb-style” (AR p.28). In Dead Line, there is a reference to the kind of tracking device that “James Bond sticks on the villain’s car” (DL p. 313). Despite all her overt and covert references to James Bond, it is obvious from TheStar.com article that Liz Carlyle’s creator is displeased with the impact of the Bond myth on the intelligence services. She says, “MI6 still finds the myth useful as a recruiting tool. Its website promises a career which, ‘like Bond’s,’ will be in the service of the country. But the myth can be harmful. The long-running conspiracy theory that MI-6 murdered Princess Diana on the orders of Prince Philip surely has its roots in Bond.” The recruiting comment that Dame Stella is referring to is found in the FAQ on the MI-6 (SIS) website, where in response to the question of how realistically MI-6 is depicted in the James Bond films, the answer is –

Dame Stella herself admits to injecting a certain amount of excitement into her novels as a concession to the literary market place. In an interview, she said, “If you are writing thrillers you’ve got to have a certain amount of violence in one shape or form. . . I try to keep my violence mild, but nevertheless things happen to Liz Carlyle that really wouldn’t happen in the life of a counter-terrorism officer.” (Note 14) In the course of the four novels, two attempts are made on Liz’s life and she winds up in the hospital twice. Not quite on a par with James Bond, but certainly within the ball park for the spy novel market. The origin of MI-6’s use of the Bond myth as a recruiting tool may very well have been Colin McColl, whose tenure as chief of MI-6 (1988-1994) overlapped Dame Stella’s tenure (1992-1996) as Director General of MI-5. In Nigel Wes’'s book on the Chiefs of MI-6, McColl is quoted as saying, “James Bond is the best recruiting sergeant in the world” (p. 214). (Note 15) Dame Stella’s characterization of MI-6 officers in her novels may well have been influenced by her interaction with McColl. In At Risk, Liz’s MI-6 protagonist is Bruno Mackay, whom Dame Stella describes as an “old Harrovian,” placing him in the context of the old saw about the alumni of three of the U.K.’s most famous public schools. The joke goes: A lady once walked into a room where there were an Etonian, a Wykehamist and a Harrovian. The Etonian called for a chair for the lady to sit on. The Wykehamist fetched one, and the Harrovian sat on it. (AR p. 11) (Note 16) McColl was a Harrovian. (Note 17) He is also the only one of the post-war Chiefs of MI-6 whose name begins with ‘Mc’. (Note 18) In his book Gentleman Spies: Intelligence Agents in the British Empire and Beyond, (Note 19) John Fisher points to an earlier possible prototype. The British Intelligence Community of the early twentieth century, says Fisher, was “a relatively closely knit social group, tied by class, education, and in some cases regimental or service affiliation.” (p. 12) In particular, he points to the Whittall family as one that had made a family business out of espionage. They were all Harrovians, and spoke Turkish, Greek, French and Italian “as well, and sometimes better than English.” (p. 13) The Gentleman Adventurer Fleming’s Bond, says Dame Stella in her article for TheStar.com, came from the British literary tradition that originated in the history of the Empire “of the gentleman adventurer playing for high stakes against devilishly cunning foreign enemies.” In the interview, she cites Richard Hannay of The 39 Steps by John Buchan as an example of such a gentleman adventurer. Dame Stella is clearly familiar with this particular Buchan novel, because, in At Risk, the attentive reader will notice a certain similarity between the search of the fields around the airbase for the approaching terrorists and the search scenes in The 39 Steps, modernized by the addition of helicopters. Her observation about “gentlemen adventures” is further expanded in At Risk, where Liz is acutely irritated by the ability of the MI-6 protagonist Bruno Mackay to pronounce “the Islamic names in such a way as to make it abundantly clear that he was an Arabic speaker. Just what was it with these people? she wondered. Why did they all think they were T.E. Lawrence, (Note 20) or Ralph Fiennes in The English Patient?” The last sentence in that paragraph makes it clear that Liz’s boss (as well as her creator) shares her opinion. (AR p. 12) Dame Stella returns to the “gentlemen adventures” again in Secret Asset, where Liz thinks to herself that “the cult of the English amateur – legacy of a Victorian public-school ethos – [is] still alive and kicking in the offshore stations of MI-6. Work hard but pretend you’re not, make the difficult seem easy – all from an era when gentlemen ran the vestiges of an empire” (SA pp. 245-6). Dame Stella revisits this topic yet once again in Dead Line, where she, incongruously, has the street-smart CIA Chief of Station use this categorization – one with which he would probably not have been acquainted – in his description of the head of MI-6. The Chief of Station was bothered by what he called “all that British upper-class stuff” when dealing with the head of MI-6. He could sense that the head of MI-6 “considered himself both his intellectual and social superior. It was irritating, too, when Fane played the gifted amateur, whose work in intelligence was just one of many hobbies, like fly fishing or collecting rare books” (DL pp. 269-270). MI-6 Cowboys vs. MI-5 Policemen Liz details her complaints about MI-6 in general and MacKay in particular in At Risk. There she cautions MacKay that if they are going to work together, he has to “employ proper tradecraft,” with “no freelancing” and “no cowboy weaponry” (AR p. 186), or “cowboy operations” (AR p. 191, 287). She is concerned not just about the danger to the asset she is handling, but also about what will happen, if the case that they are working on ends up in court. Working in the U.K. (MI-5's turf) is not the same as working in the field (MI-6's turf). If the case ends up with an arrest, she says, “and we’ve broken the law, the defense lawyer will have a field day.” (AR p. 186).  In Secret Asset, Dame Stella recasts the discussion in a more straightforward way. There she has an old-school talent spotter, who had been active before the time when open recruitment came to the security services, talk disparagingly about one of his former students who had decided to work for MI-5 and not for MI-6. When the student informed the talent scout that he wanted to work for MI-5, rather than for MI-6 – which was the talent scout’s clear preference – the talent spotter asked “if he’d really worked so hard and done so well in order to become some kind of bloody policeman.” (SA p.61) Dame Stella takes this discussion to the next level in Illegal Action. There she has Liz’s boss reflect on the differences between himself and his opposite number in MI-6. He respected his opposite number “for his intelligence and his skill at getting things done but he did not entirely trust him. The two men were products of the different cultures of their services.” The culture at MI-6 was “to train officers to be self-reliant, to work alone or in small groups, sometimes in hostile conditions, where the emphasis was on initiative and getting things done.” The culture at MI-5 was based on “working on complex investigations, in interdependent teams, where everything that was done might ultimately face scrutiny by parliamentary committee, official inquiry, the courts or even the press.” From the point of view of MI-5, MI-6 “was devious and cut corners.” From the point of view of MI-6, MI-5 “was overcautious.” (IA p. 256) In At Risk, Dame Stella puts a rather finer point on the ethical implications of these cultural differences, though she does owe a debt of gratitude to Frederick Forsyth for having previously raised the same questions found in the plot of At Risk in the plot of The Fourth Protocol (1984). (Note 21) Dame Stella can be assumed to have at least a passing knowledge of Forsyth’s work. In Secret Asset, she has Liz discover a copy of Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal while perusing the book shelves of one of the suspects in her investigation. (SA p. 256) In Forsyth’s novel, an unofficial covert operation has secretly been mounted using KGB assets to detonate a nuclear device near an American airbase in the U.K. in violation of the fictional secret fourth protocol of the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which prohibited non-conventional delivery of nuclear weapons, i.e. by means other than military aircraft or ballistic missile. The plot is foiled by the brain work of the MI-5 officer investigating the case, John Preston. In At Risk, the target is again an American airbase in the U.K., the delivery is non-conventional, and the plot is foiled by the brain work of the MI-5 officer investigating the case, Liz Carlyle. The explosive device, however, is conventional. The final scenes of the two thrillers are amazingly similar. In The Fourth Protocol, the Soviet illegal who is the “delivery man” for the bomb is killed by the SAS team with a shot to the head, even though Preston insists that they want him alive for questioning.

In At Risk, the Islamic terrorist is shot in the head by the SAS team, despite Liz’s insistence that he be taken alive.

In both novels, the reason that the bomber is not taken alive is to cover up things in the case that would be embarrassing to MI-6. With inter-service friends like that, MI-5 (Same Stella) can hardly be expected to need external enemies. Gender Gender issues are the second most prominent “organizational pathology” visible in Dame Stella’s novels. She was the first woman to become the Director General of MI-5, and the prominence of gender issues in her novels is undoubtedly a reflection of the fight that she had breaking the pink ceiling. In her article for TheStar.com, Dame Stella notes with interest that shortly after she became the first woman to head MI-5, “the character ‘M’ – 007’s boss – became a woman who was clearly modeled on me.” Dame Judi Dench’s appearance on the silver screen in the role of Bond’s boss is a clearly visible proclamation of Dame Stella’s success. In At Risk, the male half of Dame Stella’s “Bonnie and Clyde” terrorist twosome displays his disdain for the security forces pursuing them. “Well, we shall see,” he says. “Let them send their best man. They won’t stop us.” The female half of the twosome replies – not entirely unexpectedly, given the fact that Dame Stella was the first woman to be the Director General of MI-5 and that the main character of her novels is a woman – “they’ve sent their best man. Their best man is a woman.” (AR p. 304) She means Liz, of course. Dame Stella’s treatment of gender issues, however, focuses on matters of political correctness, ignoring the implications of sex as a tool of the spy trade implicit in the name “Mata Hari” and in the espionage jargon for a sex-for-secrets operation, “honey-trap,” both of which figure prominently in Voices Under Berlin by T.H.E. Hill, one of the American representatives of the new wave of insider spy fiction. There the Russians are targeting one of the Americans populating the novel with a SWALLOW, the bait in a “honey-trap.” The mystery of the novel is to discover which one of them is the SWALLOW’s target: Kevin, the Russian transcriber, Blackie, the blackmarketeer, or Lieutenant Sheerluck, the martinet? In a 2007 recruiting campaign aimed at bringing more women into the service, MI-6 declared itself a “family-friendly organisation”, which would “absolutely not” use female members as a “honey-trap.” (Note 23) There is no hint of Liz being asked to use her feminine wiles for Queen and Country in any of Dame Stella’s novels, nor is there any hint that Liz has to deal with the expectations of sex from male sources that she is handling who haven’t read the MI-6 FAQ and don’t know that “the service does not use this or similar tactics.” (Note 24) MI-5 does not address this question on their Careers FAQ, (Note 25) but perhaps they should. In Thomas Murphy’s Edge of Allegiance, yet another of the American insider spy novels, the female lead Julie complains that dealing with male colleagues in the office is not the only problem that female case offices face. They are often “sent to cultures where men think a woman is good for one thing, two if you count cooking” (p. 204). Lindsay Moran makes this point a bit more directly in the memoir of her brief career as a CIA case officer, Blowing My Cover, (Note 26) where she says: “There were few male ‘targets’ or agents who didn’t try, at least once, to introduce the idea of sex into our relationship.” And if that was not enough, Moran says that the standard cover for a female case officer being found with a male asset was to say that they were having an affair, (Note 27) which is very well demonstrated in Gene Coyle’s The Dream Merchant of Lisbon. (DMoL pp. 138-9, 147) Dame Stella is clearly aware of what a “honey-trap” is, because she references one in Dead Line. The bait in the “honey-trap,” however, is not a woman, but a man, a very slick Mossad case officer who has gone off the reservation. His target is an older American divorcée living in London who is a member of the Israeli peace movement. (DL p. 325) Though Dame Stella does not specifically term it a “honey-trap,” there is also one in Illegal Action. There the bait is a Russian “Romeo” named Dimitri, and Liz is the target of the trap. (IA p.268) Love in the Secret Service In Secret Asset, Dame Stella outlines the problems of love in the Secret Service. Liz had never dated a co-worker, because “mixing business and pleasure seemed to invite trouble.” That wasn’t to say that going out with civilians was any better. “Either they were married, thought Liz, or too inquisitive about her work – or both.” The curious ones seemed the biggest problem, because their interest in her work would never get a satisfactory answer. (SA p. 199) This problem, thinks Liz, is what results in the “Jekyll and Hyde” split personalities that her co-workers display as they shift between work and non-work mode. (SA p.108) She could only really say what kind of a day she had had if her partner was in the business too, which Liz thought was the explanation for MI-5’s “view of intra-service romances. They weren’t exactly encouraged, but they weren’t forbidden either.” (SA p. 199) In Dead Line, Liz is surprised to discover that her girl-Friday Peggy Kinsolving has a “non-work” boy-friend. “Well blow me down, thought Liz. It had barely occurred to her that Peggy had any personal life at all; she seemed so utterly caught up in her work. Good for her.” (DL p. 38) In At Risk, Liz is having an affair with Mark Callender, a married man, and a journalist with “an unerring instinct for the tradecraft of adultery.” (AR p. 5) Liz breaks off their relationship because she begins to suspect that as far as he was concerned, she was “that most chic of journalistic accessories – a pet spook[.] Even if he had said nothing to anyone it was clear that the game had moved beyond the realm of acceptable risk into crazy-land. He was playing with her, drawing her inch by inch towards self-destruction.” (AR p. 31) If he were to leave his wife and they were to make their relationship more permanent, her career with MI-5 would suffer. There would be no direct confrontation, but the next reorganization would see her reassigned to something “risk-free and unexciting – recruiting, perhaps, or protective security – until the powers that be saw how her private life worked out.” (AR p. 135)  In Illegal Action, Liz has a new lover, a Dutch investment banker with Lehman’s in Amsterdam named Piet, who came to London every third week. He wasn’t curious about her work, though she suspected that he knew what she did, as she had met him at a party given by a co-worker of hers. (IL p. 18) Their relationship ran its course. It ended when Piet’s meetings in London were discontinued and Piet met someone else in Holland. (IA p. 87) There is no discussion of the effect that her relationship with a foreign national would have on her career. From personal experience – my wife is Dutch – I can guess that Liz’s career would probably not have taken the same course as it would have, if she had made her relationship with Mark more permanent. The Dutch are a cooperating service, as Dame Stella makes clear in Secret Asset, where an MI-5 researcher calls the AIVD in Holland asking for an ID on a telephone call originating in Amsterdam. (SA p. 51) Other nationalities, however, might have produced a different outcome, as is demonstrated in Voices Under Berlin and The Dream Merchant of Lisbon, where the choice comes down to the Agency or the woman. The two potentially serious suitors for Liz’s affections whom Dame Stella continues to display on the romantic radar in novel after novel are Geoffrey Fane, the head of MI-6 and Charles Wetherby, Liz’s boss at MI-5. Fane is divorced because his wife “had been a drag on his career. She had never taken to being an MI-6 wife. She had no sympathy with his work or any wish to understand it and was merely irritated by the frequent postings abroad and her husband’s mysterious and unpredictable absences.” (DL p.51) She had “resented the constant moves round the world, the secrecy and above all the fact that as an MI-6 officer he was most unlikely to become an ambassador, so he could never be ‘Her Excellency’.” (DL p. 137) He is attracted to Liz. (DL p. 157) Gene Coyle reiterates this point in his The Dream Merchant of Lisbon, where he explains why Kathy Reilly wanted to divorce Shawn. The failure of their marriage was due “to too many years overseas in unpleasant locations and Reilly out doing God knows what at all hours of the night for the CIA.” (DMoL p. 53) Wetherby is five years Fane’s junior (DL p. 51), but is married to Joanne, to whom he is devoted, but who is terminally ill (DL p. 11). Liz’s preference is for the unavailable Wetherby. (DL pp. 51, 71) Joanne dies at the very end of novel four (Dead Line), opening the possibility of some kind of real romantic relationship between Liz and Charles. (DL p. 374) It seems that Dame Stella feels that intra-service romance is best after all. The “Special Relationship”  In her fourth novel, Dead Line, Dame Stella pushes the conflict between MI-5 and MI-6 into the background and focuses on the “special relationship” between the British and the Americans. The level of distrust on both sides is very high. It is rather reminiscent of the air of cautious distrust in the British television series The Sandbaggers (Note 28) that exists between CIA Chief of London Station Jeff Ross (Bob Sherman) and Neil Burnside (Roy Marsden) the Director of Special Operations (D-Ops) at MI-6. They are friends, but occasionally find themselves forced to work against one another. Dame Stella’s novel also has a sense of CIA/MI-5 romantic tension that recalls the love interest between CIA officer Karen Milner (Jana Sheldon) and Burnside. Normally, MI-5 would not be liaising with the CIA, but with the FBI. Liz “knew most of the FBI characters at the embassy” (DL p. 13), and has an FBI cup on her desk to prove it (AR p. 9). There has, however, been a tip about a threat to a multinational conference in Scotland which the President of the United States will attend and the CIA is the point of contact with the American Embassy for the conference. The street-smart CIA Chief of Station, known as “Bokus the Bruiser” (DL p. 27) is being assisted by an “Ivy League” junior officer named Miles Brookhaven. The Chief of Station instructs Brookhaven to “get close” to Liz, but to make sure that it she is not the one getting close to him. “These people act like they’re our best friends,” he says, but “they aren’t, right? . . . this Carlyle lady will be ‘perfectly charming’. She’ll coo and chat and give you tea. . . . She may even act like she’ll give you more than that. But when you close your eyes for the first kiss, when you open them, you’ll find that she’s swiped your shoes.” (DL p. 59-60) The Brits are no better. When Miles takes Liz out for champagne in a private “pod” on the London Eye, she wonders how he’s paying for this obviously expensive date. Her inclination is to think that he’s putting her on his CIA expense account, which leads her to wonder what makes her “worthy of such an extravagant cultivation” and what are “they hoping to get out of her?” (DL p. 113) Fane, the chief of MI-6, suspects Brookhaven, because he was the one who originally contacted the source who produced the tip about the threat to the conference, and handed him off altruistically to MI-6. Fane has Brookhaven investigated through MI-6 channels. (DL pp. 158-9, 170) That investigation leads nowhere, but the suspicions remain. The plot thickens when the CIA Chief of Station is photographed in a clandestine meeting with an undeclared Mossad officer. (DL pp.188-9) The Brits suspect that the Chief of Station has been turned. (DL pp.367, 369) The clear implication of this discovery, in the historical context of CIA/MI-6 relations, is that MI-5 has uncovered the American equivalent of Philby, Burgess and Maclean. Philby was the MI-6 liaison between the British Embassy and the newly formed CIA. Maclean was the MI-6 officer who had been assigned to the British Embassy in Washington from 1944-1948, just before Philby arrived in 1949. Burgess was assigned to the embassy in Washington simultaneously with Philby. Suspicions are quickly straightened out by direct contacts at the highest level. The head of MI-5 flies to Washington to meet with the head of security for the CIA. The Chief of Station was not being run by the Mossad officer, but was running the Mossad officer, unbeknownst, in violation of protocol, to the British. Apologies return the balance of mistrust to an even keel. It is hardly a good way to run a special relationship, but it does ring true to life. Dame Stella’s novels offer an unusual insight into the life of intelligence officers on the other side of the Atlantic, and should certainly be added to the reading list of Dr. Wiant’s course on spy fiction at the NDIC, in conjunction, of course, with the American contributions to this new sub-genre, as the comparison of the two sometimes brings the issues they are treating into sharper focus. For spy thriller fans, Dame Stella has done a good job of embellishing the action, and I would be surprised if one of her books did not eventually make it to the silver screen. In Neil Simon’s Chapter Two, (Note 29) George explains to Jennie that he writes his spy novels under the name of Kenneth Blakely hyphen Hill because his “publisher said spy novels sell better when they sound like they were written in England.” (p. 46) Simon’s joke from the 1970s seems prophetic in the twenty-first century when applied to the new sub-genre of insider spy fiction. Although there are more American insiders writing this kind of novel, none of them have had a second book published, despite the fact that the American novels are equally interesting. Dame Stella, on the other hand, is readying her fifth book for publication. What a difference being English makes, not to mention being the former Director General of MI-5. Notes ~ Note 1 – Philip H.J. Davies, “Was Mackintosh a Spy?”, OpsRoom.org. Last viewed on 21 November 2008. Note 2 – For a more detailed discussion of the American novels, see Hooker, “An Emerging Trend in Spy Fiction – Retured James Bonds Become Ian Flemings”, in the Spies in History & Literature section of this website. Last viewed on 16 November 2008. Note 3 – Jon A. Wiant, “Spy Fiction, Spy Reality,” Learning with Professionals: Selected Works from the Joint Military Intelligence College, Washington, D.C., 2005, pp. 111-123. Note 4 – Formerly known as The Joint Military Intelligence College. Note 5 – See: Hooker. Note 6 – AR p. 10, SA p. 18. Note 7 – “Bond: Daring spy or obsolete duffer?”, TheStar.com. Posted 17 May 2008. Last viewed on 14 November 2008. Note 8 – “James Bond’s Aston Martin DB5 voted most iconic car”, BoxWish.com. Posted 27 October 2008. Last viewed on 15 November 2008. Note 9 – “James Bond car sold for over £1m”, BBCNews.com. Posted 21 January 2006. Last viewed on 15 November 2008. Note 10 – “List of James Bond firearms”, Wikipedia. Last viewed on 20 November 2008. Note 11 – Notting Hill (1999) with Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant, run time: 124 minutes, quote at – 1h 50m. Note 12 – Ian Fleming, From Russia with Love, New York; Signet Books, 1957. Note 13 – “FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: How can I offer intelligence to SIS?”, SIS.gov.uk. Last viewed on 15 November 2008. Note 14 – Dan Williams. “Ex-MI5 chief Rimington treads carefully as novelist”, UK Yahoo News. Posted 27 October 2008. Last viewed on 15 November 2008. Note 15 – Nigel West. At Her Majesty’s Secret Service: The Chiefs of Britain’s Intelligence Agency, MI6, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2006. Note 16 – See also: Christopher Tyerman. A History of Harrow School, 1324-1991, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 490. Note 17 – West, p. 124. Note 18 – See the Wikipedia list of Chiefs of the SIS. Last viewed on 20 November 2008. Note 19 – John Fisher, Gentleman Spies: Intelligence Agents in the British Empire and Beyond, Sutton Publishing, 2002. Note 20 – Read the Wikipedia article on T.E. Lawrence. Note 21 – Also a movie of the same name (1987) with Michael Caine and Pierce Brosnan. Note 22 – Frederick Forsyth. The Fourth Protocol, New York: Viking, 1984. Note 23 – James Slack, “MI6 woos ‘Jane Bonds’ with offers of family-friendly employment”, Mail Online. Posted on 14 May 2007. Last viewed on 15 November 2008. Note 24 – The MI-6 FAQ for “Women in SIS”, SIS.gov.uk. Last viewed on 15 November 2008. Note 25 – MI5, “About Working for the Security Service”. Last viewed on 15 November 2008. Note 26 – Lindsay Moran. Blowing My Cover: My Life as a CIA Spy, New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons, 2005, p.200. Note 27 – Moran, p. 186. Note 28 – Read the Wikipedia page for The Sandbaggers. Last viewed on 21 November 2008. Note 29 – Neil Simon, Chapter Two: A Comedy in Two Acts, Samuel French, Inc., 1979. Dame Stella Rimington’s novels are available in bookshops everwhere, as well as these online merchants ~

Amazon U.S.

|